What is patient engagement?

To achieve patient-centered health, get to know the three “e’s” of engagement

On paper, “patient engagement” has become something of a buzzword. Defined as a broad approach for the healthcare industry to motivate patients to be active participants in improving their own health and wellness, the phrase is so vague that it can easily be misinterpreted.

Upon deeper investigation, you will find that there are distinct but highly interrelated aspects of patient engagement. As a result, what engagement means for one set of stakeholders may be vastly different for another.

Here’s a recent story to help illustrate the point:

A tale of two “E’s”

We recently collaborated with a team of behavioral scientists at a large pharmaceutical company. Our collective mandate was to create a set of prototypes focused on leveraging specific behavior change techniques (BCTs) to achieve a particular health goal (or “outcome,” as they say in healthcare).

While medical care accounts for only 10-20% of a person’s health outcomes, an estimated 40-50% of health outcomes are attributed to behavior (diet, exercise, alcohol/tobacco use, medication adherence, etc.)

Utilizing digital platforms to drive better health outcomes is a field with enormous potential. Between 2021 and 2022, U.S. consumers doubled their use of healthcare wearables, such as blood pressure monitors and smartwatches. As an article in Translational Behavioral Medicine notes: “The rapid expansion of technology promises to transform the behavior science field by revolutionizing the ways in which individuals can monitor and improve their health behaviors.”

As UX professionals, we are experts in how individuals interact with digital media, what makes for “sticky” experiences, how to make information readily digestible, and how to design interfaces that encourage users to take action quickly and easily. As behavioral scientists, our collaborators were experts in knowing what makes people tick, what drives behaviors, and, most importantly, how to instigate behavior change.

Theoretically, we all had a really good sense of our respective areas of expertise. But when it came to the prototypes themselves, it became murky pretty quickly in terms of who should lead the conversation around various parts of the experience and related feedback, and it became apparent that we needed a clear conceptual separation of concerns. We drew a line between what we called “little e” and “Big E.”

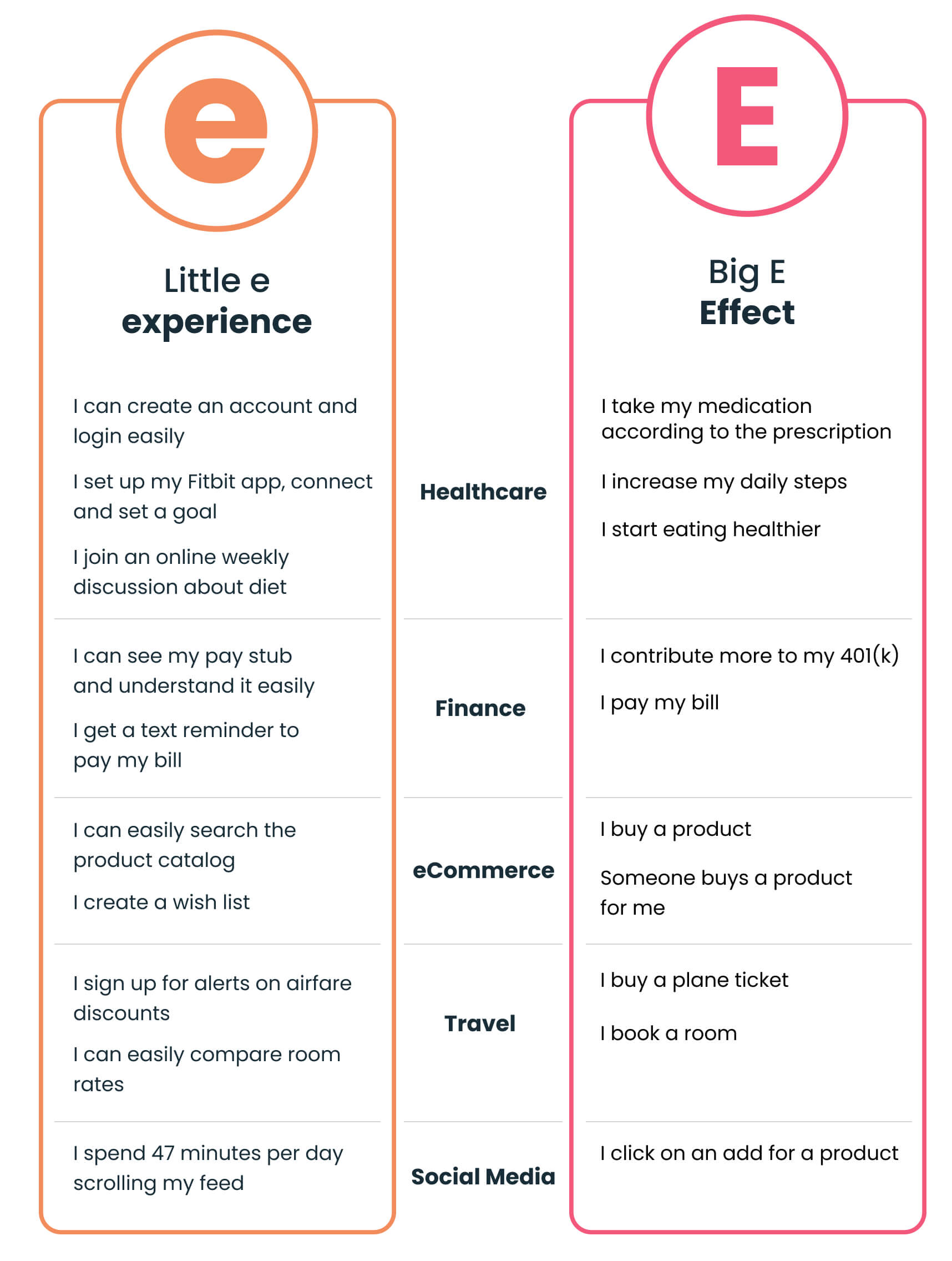

As UX professionals, our focus was on the “Little e” — engagement with the experience itself. The behavioral scientists were tasked with narrowing in on the “Big E” — the desired effects of the experience — enacting a behavior change (exercising more, doing a group meditation, etc). We used this distinction all the time: Little e = experience, Big E = effect.

The term “little” was not intended to demean our work in any way, but rather keep the focus and primacy on what we were really trying to accomplish with these prototypes: the Big E of positive, healthier behavior change. We also collectively acknowledged that good “little e” is a clear prerequisite for impactful “Big E.” After all, you can’t get to the behavior change with poor UX standing in the way.

To help illustrate the distinction across industries beyond healthcare, here are a few examples:

One “E” to rule them all

Before we design an experience, it’s crucial that we infuse another “e” into our process — the “Easy E.” What are we talking about? No, we’re not referring to the late “Godfather of Gangsta Rap,” Eric Wright (aka Eazy-E). We’re talking about empathy — the first recommended step in the design thinking process.

Empathy is “easy” in that most of us have the capacity for it. Like any muscle, for some, it may be in better shape than others — and for some, perhaps overworked — but our ability to connect with each other is part of what makes us human. It is widely acknowledged that a health professional’s ability to empathize with a patient leads to better therapeutic results. Patients are more likely to follow their treatment plan and practice self-care when they feel heard and understood. However, while empathy itself is a natural human instinct, incorporating empathy into patient experience design is not, in fact, easy.

One of the reasons empathy can be lacking in a healthcare setting is that providers are often under enormous pressure with limited resources. Prioritizing empathy requires putting space in the budget for proven tools and practices designed to help us understand the patient’s needs: interviews, field observation and shadowing, and creating user personas and journey maps. We take time to read and listen to relevant stories. We invite users to participate in design processes. We show early ideas to users and incorporate their feedback through validation testing. For example, in one project we learned that patients care much more about being in groups with people with whom they would be comfortable in everyday life, rather than people who have the exact disease subtype or prognosis as them.

And we make sure the entire team, from leadership to the front line, has spent time with and internalized the research, personas, and journey maps. We name our personas and create profiles of them so that when we put them up on the wall during meetings they are there with us. We can quickly point to them and ask: “How would Sharon Slipsalot find this feature?” or: “How would Danny Debilitated be able to access this experience at this point in his journey?”

While digital health has advanced dramatically post-Covid, technology and innovation cannot replace human connection. Empathy is the root of all human-centered design, and when you invest in creating empathy, you ensure that the delightful “little e” and impactful “Big E” you are striving for have resonant, lasting results.